The founder of BRM was Raymond Mays CBE (1899-1980), pre-war racing driver, founder of English Racing Automobiles (ERA) and pioneer of the commercial motor racing industry. His post-war vision was to boost British prestige by creating a British Grand Prix car capable of taking on the world and beating the might of the Germans and the Italians driving Alfa Romeos, Ferraris, and Maseratis. He persuaded the great industrialists and engineers of the time to support his vision and The British Motor Racing Research Trust was established in 1947 to promote, finance and develop BRM.

The story had begun in the 1940s with a powerful and frighteningly complex V16-engined car designed to take on the European manufacturers that had, for so long, dominated Grand Prix racing.

Based at Bourne in Lincolnshire near Mays’ home, a new racing car manufacturer, ERA, was born. Bet-ween 1934 and 1936, 17 cars were built, becoming familiar on the circuits of Europe and racking up many race and hillclimb victories. With the factory Bentleys having withdrawn from Le Mans 24-hour racing, it could have been a bleak period for the British motor industry had it not been for ERA.

The Second World War then swept away the dominating German Grand Prix cars. After the war, the Italians, led mainly by Alfa Romeo, moved back to the forefront of racing ahead of the French. The world had changed and for Mays that meant new opportunities at the top level of motor racing. The British motor industry, he felt, could surely be brought together to produce a world-beating Grand Prix car. For 40 years, foreigners had ruled Grand Prix racing and that was surely long enough. Mays and Berthon’s voiturettes had been ‘English’. Their new cars would be ‘British’ – ‘British Racing Motors’.

The UK was Europe’s largest and the world’s second biggest manufacturer of cars just before and after the war. The British motor industry was independently minded and had successfully applied itself to the war effort.

RM felt that, with the clean sheet that a post-war world offered and the support of Britain’s motor industry, he could build a racing car that would, at last, take the country to the pinnacle of Grand Prix racing. In March 1945, with the end of the war in Europe a few weeks away, he wrote to leaders of the British industry. The idea was no more than just that, an idea. It became known as the Mays Project – but he reckoned on a ‘superiority (that) should be perpetuated as a gesture to the technicians and servicemen who have made our victory possible’. He had little idea of the ‘vast expenditure’ that would be required.

Mays wanted the British motor industry to support his concept by developing and supplying components, as well as provide funding.

Not everybody at first shared May’s vision but then, on the same day, he received two replies each pledging an initial £2000, of which £1000 would be in kind. One of these was from electrical manufacturer Joseph Lucas. The other was from the imposing, religiously devout Alfred Owen of the Darlaston-based engineering company Rubery Owen.

Established by the Rubery brothers in 1884 as an ironworks manufacturing fences and gates, this had become Rubery Owen when Alfred’s father, also called Alfred and a trained engineer, joined it. The company had subsequently expanded into such areas as aviation engineering and motor frames.

At its height, the company would employ 17,000 people worldwide, 5000 skilled workers at its 74-acre site in Darlaston alone, while up to the 1980s most of the cars built in the UK would feature a Rubery Owen product, whether a wheel or a simple bolt.

Rubery Owen continued to grow and became at one stage the largest privately owned company in Europe, evolving from its manufacturing heritage to operate in several different market sectors from materials testing and the design and manufacture of bespoke testing machines, battery management technology through to the manufacturing, formulation, blending and packaging of chemical liquids. It was, and is, a remarkable company that would not only ensure the continuation and eventual success of BRM but also be involved in the development of Donald Campbell’s World Land Speed Record Bluebird, another project that stirred the patriotic soul.

Alfred liked what Mays had to say. ‘This is important because it is impossible to know where pioneering work like this will lead us,’ observed Owen, who, like the older Mays, had attended Oundle School in Northamptonshire.

Sir Alfred admitted that he had no particular interest in motor racing prior to 1947, although he knew that Rubery Owen had made chassis frames for the speed record cars of Malcolm Campbell and others during his father’s time.

RM visited Lucas and Owen on the same day, first charming the boss of the electrical concern in Birmingham. Lucas asked Mays how much he wanted, the reply being £1000 plus the free manufacture of parts. Lucas agreed, promising, in addition to the cheque, £4000 worth of equipment. As Mays then drove on to Darlaston, Lucas rang Owen, as the latter recalled, to say that he was ‘prepared to allocate £5000 to the venture if you’ll do the same.’

Owen was impressed by Mays and agreed.

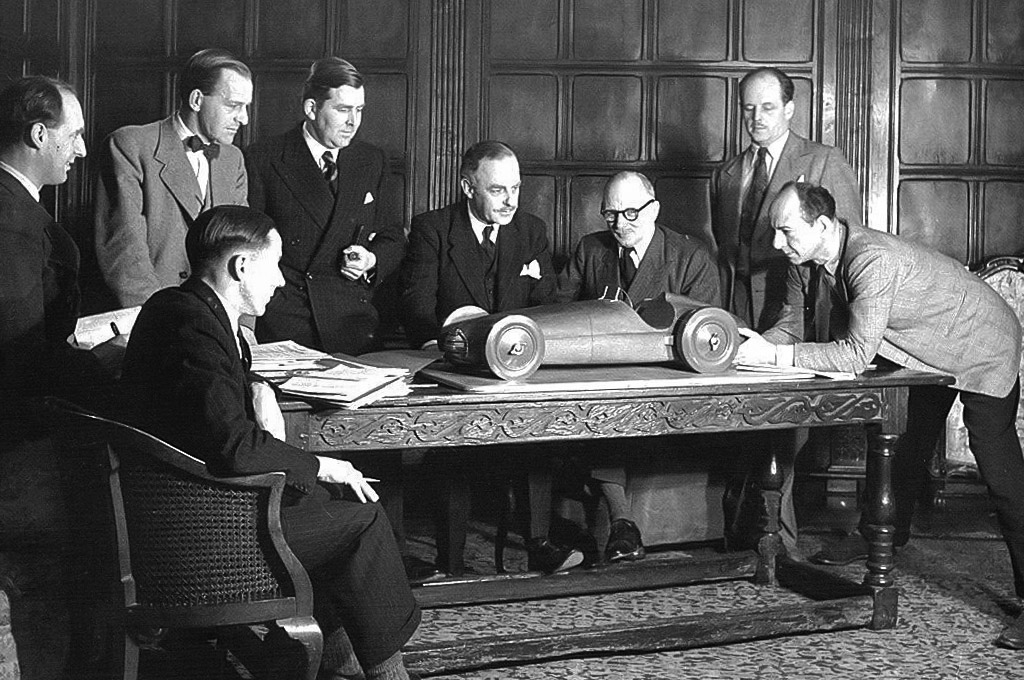

Once Owen and Lucas were on board others began to take interest and, by March 1946, Mays had collected £20,000 in cash and the promise of £20,000 worth of free work. Twenty-two companies were now involved – this would grow to more than 350 – and The Times newspaper had even run a leader in praise of the idea. Now RM had to deliver.

The original Automobile Developments Ltd, Bourne, works drawing of the projected BRM V16 engine’s upper crankcase is dated ‘28-4-48’. This historic piece transcends mundane technical drawing and for any motor racing enthusiast is surely a carefully crafted and historic work of art.

The project was originally launched under the title of Automotive Developments Ltd, a company that RM and PB had formed in 1939. However, in 1947 some its backers came together to control its future using the name British Motor Racing Research Trust (changed in late 1950 to the British Racing Motor Research Trust), with the unswervingly patriotic Donald McCullough, known as the question master of radio’s Brains Trust, as chairman. Owen was one of the committee members alongside such as Bernard Scott from Lucas, David Brown, the head of Aston Martin and Lagonda, and Tony Vandervell of bearings manufacturer Vandervell Products.

Two years later, a new management board saw Automotive Developments renamed British Racing Motors Ltd. What was to become one of the most famous sets of initials in British motor racing had been established.

Extracts from Racing For Britain by Doug Nye and Ian Wagstaff